RIVER JOHN

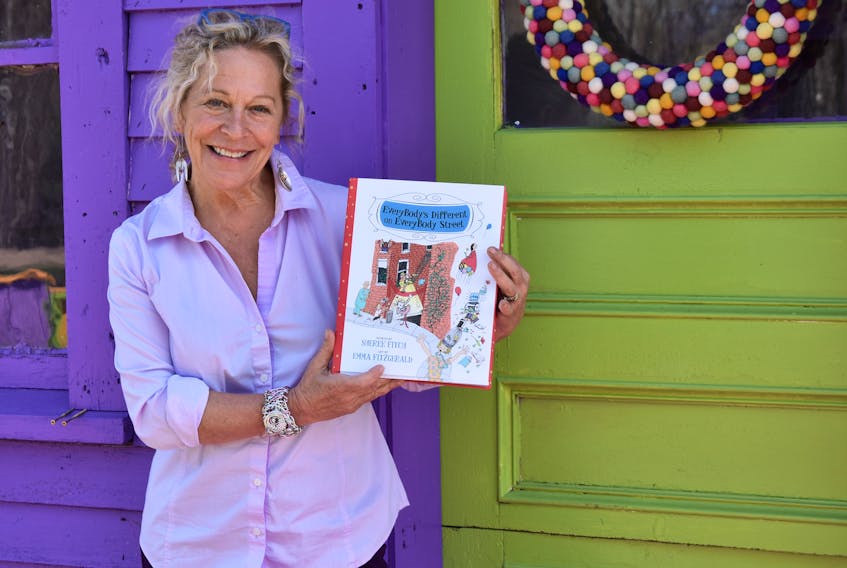

The April release of Sheree Fitch’s newest book, EveryBody’s Different on EveryBody Street has been a significant milestone for the River John-based writer

Although Fitch is no stranger to the publishing world, her newest book – a whimsical, illustrated poem that celebrates diversity in the world – has a great deal of personal meaning to her. The book is dedicated to her son, Dustin.

Fitch described the timing of the release of her book as “bittersweet,” since after a long struggle with mental illness, her son died on March 2 – a loss that Fitch acknowledges in the epilogue of the book.

It goes without saying that the last couple of months have been a time of recovery for Fitch and her husband, Gilles. Fitch noted that it “feels like yesterday” that the shock of Dustin’s death came into their lives.

“When the shock wears off, you feel your pain in different ways,” said Fitch. “When you face death, you come together with family and friends to remember what you loved. It sounds trite, but my memories are with the ‘shiny Dustin,’ the living Dustin – the one who said things like ‘Mom, you need a hug.’”

EveryBody’s Different on EveryBody Street, illustrated by Emma Fitzgerald, serves as a sort of prayer to her son’s memory – something she believes properly honours his legacy, and the difficulties in his life he faced with mental health.

“(Dustin) struggled all his life. It was a long journey, and he taught me everything I know about love,” said Fitch. “Loving someone with mental illness brings out everything you have to keep facing in the face of that mental illness. It teaches you how to stay close and stay out of the chaos – but to let them know they’re loved.”

EveryBody’s Different on EveryBody Street was originally conceived 17 years ago, for commission from the Nova Scotia Hospital Foundation, now known as the Nova Scotia Mental Health Foundation.

Fitch said the foundation requested she write a poem that would educate and start a conversation about mental health.

“They came to me and said, ‘Sheree, we want you to write something we can turn into a booklet to raise money for our organization, but also so we have something we can go to schools with, put in the hands of teachers, and begin conversations and create space to talk about mental illness, addictions and mental health.’ I didn’t accept for two reasons,” said Fitch.

Fitch said the first was the fact that “as a writer, you can’t wait for the muse to strike and be inspired. I didn’t want to be contrived, didactic or preachy. I didn’t want to hit kids over the head with it.”

Fitch said she would rather leave space for conversation to begin, which was the intention of her eventual creation of the lighthearted verse structure in which EveryBody’s Different on EveryBody Street is written.

“A children’s book should delight and not instruct,” she added.

Fitch also hesitated to write the book when requested 17 years ago because she was uncertain how, or whether she wanted to talk about the subject of mental health. There was as much of a taboo about the subject then as there is now – and it was real to her, given Dustin’s struggles.

As much as she wanted to help break the stigma and start a conversation to help people isolated and contending with mental illness, Fitch hesitated to write about the issue. Then, in 2001, her husband helped convince Fitch it had to be done – and that she was the one to do it.

“It’s rampant… and a serious epidemic. People are hesitating to talk and there’s a lot of shame –and taboo – around it,” said Fitch.

She noted that her husband told her, while on a trip to New York that it was “precisely the right time” to have a conversation, and that she was “precisely the right person” to write a poem to spark it.

Fitch, when she originally wrote the poem, asked her son’s consent to mention him – a request to which he replied, “mom, you have to.”

“We have to stop being ashamed, and see mental illness for what it is – an epidemic in society,” said Fitch. “Often, they’re dealing with it for much of their lives, and it’s like living from crisis to crisis. Some people are lucky if they get stable months and years. A lot of people out there are needing help yesterday, and not getting it until next year.”

Fitch believes it’s not all bad news – she sees progress, and is hopeful her writing can contribute.

“It’s much better than it was when my son was 12 and people were calling his depression ‘a phase,’ instead of depression. Now people get some of the help they need,” she said. “People are now aware that the system needs to be fixed I a lot of ways – there are a lot of people suffering.”

Another moment of inspiration came during that trip to New York, walking the streets of the city and beholding “a sea of humanity."

“I looked at the diversity of the people in New York, at their different faces and eyes; the different way they were dressed. It was a moment of me thinking people are beautiful – and there’s a oneness in seeing that,” said Fitch.

During that revelation Fitch’s imagination kicked in and she began to form the verse in her mind, celebrating the diversity of the crowded streets.

“I had a sense of interconnectedness, and what I did was I heard the rhythm of the first verse. I got the rhythm in my head, and started to work on it.” The rest of the poem flowed from that, and became a celebration of diversity and getting along.

Although writing the EveryBody’s Different on EveryBody Street was the first step toward a conversation about mental illness, Fitch insists that the conversations that result are more important than the book itself.

“It takes people who care to make the book have the life it’s meant to have. You don’t make a lot of money as a poet, but what you hope is that you connect with another human being.”