Rosalie MacEachern

Special to The News

The tragic legacy the McGregor mine explosion carries on 68 years later, more as an absence than a presence in the lives of three men who lost their fathers that day.

Nineteen miners, referred to in media reports as “the cream of the pit” died in an explosion deep in the mine on the afternoon of Jan. 14, 1952.

One of them was Bain Nicholson, 34, a Trenton native who married into the Stewarts, a Stellarton family with long ties to coal mining. He lived on Poole Avenue with his in-laws at the other end of a former company house. He was a father of three – two daughters and a son, Garfield Nicholson, who was almost seven.

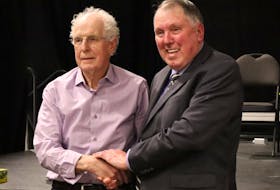

Also killed in the fiery blast was Edward MacCallum, 36, of Brown Row at the top of Acadia Avenue. His parents came from North River, Colchester County, and he, too, married into a coal-mining family, the Fitzgeralds from Red Row. MacCallum had two young sons: Ed who was 22 months and Clifford, better known as Buzz, who was 10 months. His daughter, Grace, was born in March, two months after the mine exploded.

Nicholson remembers his father and he remembers the day he died but they are a child’s memories, more vivid snapshots than a continuing stream. He remembers he and his older sister were told to leave school early and go straight home.

“I can’t remember if my mother was at the house when we got home but we heard people saying the mine had exploded. We walked up to the pithead. There were police there but it wasn’t roped off like when Westray blew. It seemed the whole town was there and maybe it was no place for a young child but I am glad I was there.”

He also remembers being there when draegermen carried dead miners out on stretchers covered by army blankets, but he has earlier, happier memories of running across Acadia Avenue to meet his father and other miners walking home from the pit.

“He’d always give us his last sandwich, wrapped in wax paper but black with coal dust by then. Miners always left something in their lunchboxes in case they were stuck in the mine but they’d give it away to the kids on the way home.”

Looking across his backyard on Hoyte Avenue, Nicholson can picture his father and other miners in the alley between Hoyte and Poole. He remembers them drinking and playing horseshoes on weekends.

“There would be a lot of laughing and hollering. Sometimes there were arguments and the odd fight might break out, but it was just blowing off steam. They’d be the best of friends on the way back to the pithead.”

Another memory is of his father helping to put coal furnaces into homes in The Asphalt.

“A group of miners would go from house to house, digging the cellars out for the furnaces. I had a little cart and I’d be following my father around with a little load of dirt.”

The MacCallums were too young to have any memories of their father. They are not sure how long he worked as a miner but he was killed seven years after being discharged at the end of the Second World War. He had been five years a soldier, part of it as a prisoner of war in Germany.

“As far as we know, he didn’t plan to stay in the pit. They were going to buy a property at Bear Brook Bridge and he was going to be a woodworker,” said Buzz, noting his father built some of the furniture in their home on Brown Row, pieces he wishes he still had.

The MacCallums know little about their father because their mother, Bertha, never spoke of him.

“She was a saint of a woman but that was something she would never talk about, not even to speak his name when we were growing up. When we were young I think she lived just to see the three of us grown. She worked at two stores on Acadia Avenue and later she got a job as a cook at the vocational school,” said Ed.

One of the few personal things they know about their father is that he loved sports.

“Buzz and I always liked sports so we have that in common with him,” said Ed.

It is through extended family or neighbours that they know anything of him, though Ed was once contacted by a woman whose husband had been a prisoner of war with him.

At the Nicholson home, it was not much different.

“My grandfather or my uncles would tell me little things about my father but my mother never spoke of him, not even later in years. She had a small widow’s pension and she took in washing and did wallpapering to make ends meet.”

He also remembers being older and telling his mother, Beryl, he was going to apply for work at the McBean Mine in Thorburn.

“She made it plain she didn’t want me working there and I think she went further, telling people not to hire me. It was hard because there was no other work at the time. I went out west and worked in the coal and hard rock mines in Alberta and British Columbia.”

He never minded the work, enjoyed the camaraderie of the mines and the hard rock money was good, but after six years he came home because his grandfather was failing.

“Papa had been like a father to me after my father was gone. He was an old miner who’d been smashed up in the pit. He was trapped one time and somebody put a pick through his back trying to shovel him out.”

Both Nicolson and the MacCallums credit strong mothers, extended family and good neighbours with filling as much of the loss as possible.

“We had nothing but neither did most so we didn’t feel sorry for ourselves. There were other families around us who had lost fathers in the mine. As kids I don’t suppose we thought too much about what it was like for our mothers,” said Nicholson.

The MacCallums say they wondered more about their father as men than as children because they could always count on an uncle to fill in at a father and son banquet or a neighbour to take them fishing.

“The Fitzgeralds and our father’s sister and her husband were really good to us. One aunt and uncle took Ed and another took me for a while until Mom could get back on her feet after Grace was born. There were always relatives around our house,” said Buzz.

One of Buzz’s sons often questioned him about his father, unable to understand why he knew so little.

“We just didn’t talk about him and I wish we had. When I went to work for Sobeys my supervisor was a guy who’d also lost his father in the McGregor but we didn’t talk about it.”

There is one time in particular when their father weighed heavily on Ed’s mind.

“I was with the Stellarton fire department, standing by when the dragermen went into the Westray mine. I was sure thinking about him that night.”

When the Pioneer Coal property in Stellarton is restored, Nicholson and the MacCallums would like to see some sort of monument placed above the McGregor pit, in memory of the 19 men who died and the dragermen who went down 6,500 feet to return their bodies to their families.

Rosalie MacEachern is a Stellarton resident and freelance writer. She seeks out people who work behind the scenes on hobbies or jobs that they love the most. If you know someone you think she should profile in an upcoming article, she can be reached at [email protected]