PICTOU LANDING, N.S. — Hundreds of people marched from Pictou Landing First Nation to a bridge on route 348 spanning a narrow point of what used to be a tidal estuary.

At this point effluent is discharged into the Northumberland Strait after going through Northern Pulp’s treatment facility called Boat Harbour.

“When you drive by, you can actually see how beautiful this is,” said Chief Andrea Paul, speaking to the crowd on Oct. 4. “This is something we haven’t been able to enjoy in 52 years.”

Many of the people who spoke that day underscored the community’s decades-old struggle for this estuary, and as new historical research now shows, that the fight for A’se’k by the Mi’kmaq has endured for centuries.

Through collaboration with Pictou Landing First Nation, a PhD candidate at the University of Saskatchewan named Colin Osmond has been making information found in the historical record more accessible to the general public.

“I don’t want this stuff locked up on my computer forever because it’s not useful that way,” Osmond said in an interview.

Last summer Osmond came to Pictou Landing with local historian John Ashton to take part in a week-long session with the community elders.

There, Osmond presented research which he has recently published summarizing a trend in the historical record which reveals a 200-year-old story of the Mi’kmaq defending their sovereignty over A’se’k.

“He came in very humble and he made a really big impact on our elder group,” said community member and Boat Harbor liaison, Michelle Francis Denny about the session which took place at the community training centre.

“I think it brought us closer together in terms of really understanding how settler colonization has translated into our current fight,” said community member and Boat Harbor liaison, Michelle Francis Denny.

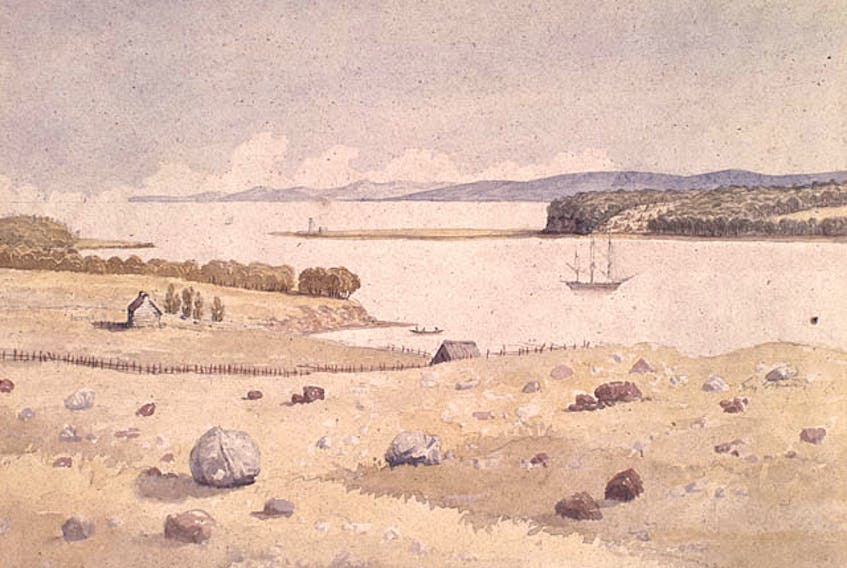

Indeed, the first examples of settler encroachment on the land around A’se’k that gets highlighted in a recently published article by Osmond date to the arrival of the Hector, which brought the first wave of highland settlers to Nova Scotia in 1773. At the time, the Mi’kmaq people were already settled at a village site located between the estuary and the entrance to Pictou Harbour.

Shortly after the Ship Hector’s arrival, unfolding wars in the United States would impact land use in a developing Pictou County, and, as Osmond writes, ‘hapless colonialists’, would attempt to survey and sign away a key region of Mi’kma’ki.

The recipients of this new land were to be the 82nd Regiment of Foot, a recently disbanded regiment of soldiers from the American Revolutionary War which had begun two years after the first highland setters had arrived.

Few of those soldiers came, and, as Osmond writes, the settlement of Pictou in the early 1800s was isolated and a long way from Halifax, the centre of colonial power in Nova Scotia.

At that time, the British colonial government looked to strengthen their relationship with the Mi’kmaq, seeing them as potential allies in the event of an American invasion.

However, the Mi’kmaq remained neutral, refusing gifts from Crown representatives and maintaining a strong political and military negotiating position in the early years of the 18th century.

“As a result,” Osmond writes, “the Mi’kmaq were mostly able to live in the region as they had for thousands of years, only now with a market for their labour and goods in the village of Pictou.”

In the face of greater colonial settlement, by the mid-18th century the Mi’kmaq were making a more concerted effort to maintain their claims to A’se’k.

Map from the 1879 Illustrated Historical Atlas of Pictou County, and it reflects changes to the reserve up until 1878. The section that borders Moodie Cove (rectangular with wigwams on it) is the original reserve created in 1864.

Then, in 1864 the Mi’kmaq secured the Fisher’s Grant Indian Reserve, securing a 50 acre-plot of land against further settlement.

By 1928 they would grow that 50 acres to 400 acres, “a testament,” Osmond writes, “to the Mi’kmaw ability to maintain and increase their territory even in the most unlikely colonial odds.”

In an interview, Osmond said that he hopes his article can give everyone some context for why A’se’k and the 2015 Boat Harbour Act matters.

“Historically, the Government of Nova Scotia and the Government of Canada have let down the people of Pictou Landing First Nation,” he said. “I think the Boat Harbour Act, as it stands now, is an opportunity to flip that history, to do the right thing and change the way that people think about this history.”

Over in Pictou Landing, Denny feels the same way.

“When I saw Colin’s article it really hit me that this goes way beyond 53 years,” she said. “And they got what they wanted in the end. They got A’se’k, and look what they did to it.”