Above a Crossroads, Cumberland Co., garage where two mechanics worked on a big diesel machine Friday, Dwayne MacGillivary sat at a worn desk pondering what to say to his operators.

He’s been getting the same question from the men who run the two bunchers, three processors, two forwarders and six tractor-trailers for LG MacGillivary & Son Lumbering Ltd.

“I’ve got people coming and telling me they’ve got a job offer and should they take the opportunity,” said MacGillivary.

“What am I supposed to tell them?”

He doesn’t know what to tell them.

Because he doesn’t know if the Cumberland County forestry outfit started by his grandfather in 1954 will exist past January 2020 – the legislated closure date for highly controversial Boat Harbour effluent treatment facility owned by the province and leased to Northern Pulp.

All he knows is what he and the rest of the province heard from Paper Excellence Canada chief executive officer Brian Baarda last week.

“If the government does not give us enough time to complete the new facility, we will have no choice but to permanently cease operations in Nova Scotia,” said Baarda of the projected year-long gap between the deadline for Boat Harbour’s closure and the anticipated earliest possible completion of its proposed replacement.

“If we do not get an extension from the government, that will mean we shut down operations in Nova Scotia.”

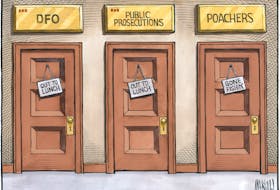

So far the government has held the line on not granting an extension.

“It’s the uncertainty that’s causing the snowball effect”

The Pictou Landing First Nation, which has housed Northern Pulp’s toxic legacy in its backyard since the mill opened, has repeatedly been promised by politicians of all three stripes that it would be closed.

It only managed to get the legislation forcing the 2020 timeline on the mill to build a replacement through negotiations after a pipe ruptured spilling 90 million litres of untreated effluent into a wetland beside the community.

As the stalemate draws on between the government and a mill that has a former premier (John Hamm) as the chair of its board of directors, uncertainty reigns.

Ninety-eight per cent of the harvesting done by LG MacGillivary’s 18 employees goes to Northern Pulp.

MacGillivary has put off the purchase of a processor and a porter – each worth north of a half million dollars. Woodland owners are jockeying to get their properties cut this summer out of fear their value will drop through the floor after Northern Pulp shuts.

“It’s the uncertainty that’s causing the snowball effect,” said Mike Fields, branch manager for A.L.P.A Equipment in Truro.

“If people knew it was going to shut for a year then restart they could make plans accordingly, but if it just shuts, it will be devastating.”

A normal year would have seen him sell five large pieces of forestry equipment by April. This year he’s sold one.

To look at how we got to such an intertwined and therefore interdependent forestry industry, The Chronicle Herald went to Spencer’s Island.

It’s the stomping grounds of both the MacGillivarys and Pat and Peter Spicer.

And it’s home to two very different forms of forestry that operate side-by-side but depend equally on the same markets.

Descent to forestry

America’s war of independence went poorly for loyalists like Lieut. Robert Spicer.

His payout for his service to England’s army and its failed attempt to keep the colonies under royal toe was a rolling land of towering red spruce looking out over the Bay of Fundy.

“He built his first cabin just across the road where dad built the house in which I was raised,” Spicer’s descendant said on Friday.

Peter Spicer is the seventh generation of his clan to make a living cutting the lands granted to Lieut. Spicer in 1786.

And it remains an intact forest.

The Spicers and the other families who joined them along Greville Bay have always relied upon the red spruce growing in the well-drained and fertile basalt soils of ancient volcanoes.

Fog rolling in off the Bay of Fundy keeps the land moist and perfect for the softwood that doesn’t reach maturity until it is nearly 200 years old and can live for four centuries.

Posts still jut out of the gravel bar from the sawmill and shipyard that were wiped out in 1954 by hurricane Edna.

For the majority of its history, Spencer’s Island didn’t rely upon sawmills and pulpmills hundreds of kilometres away.

Teams of men lived in camps behind the community cutting the red spruce on hills and gulches that still bear their names. Signs made by her daughters for Christmas a few years back mark the nearly 30 kilometres of woods roads Pat maintains with an excavator on their 600 hectares. There’s Ike’s Choppins, the Preachers Camp Road, The Ship Timber Gulch and more.

Those long straight-grained logs were hauled out by horses to be milled, shaped and somehow turned into great ships by the Spencers Island Company.

Its last full-rigged ship was launched from the bar below Spicer’s home in 1891.

Under the command of brothers Capt. Gerald Spicer and Capt. Dewis Spicer the Glooscap circumnavigated the globe her first year, carrying cargo to Liverpool, Cape Town, Australia and New York.

Steel, steam and diesel replaced red spruce planks and canvas and saw Spencer’s Island export its lumber primarily via truck.

The mill was rebuilt after hurricane Edna in behind the community but its fate was sealed too as this province’s forest industry centralized.

Enter the pulp mill

In 1929 Bowater Mersey opened a large pulp mill outside Liverpool and added a new word to the province’s forestry lexicon – pulpwood.

Larger, more efficient saw mills grew throughout central and southern Nova Scotia, turning the larger logs cut as part of supplying the mill into construction lumber.

In the 1960s Scott Paper built a kraft pulp mill at Abercrombie Point in Pictou County, consuming immense amounts of low-grade wood and encouraging the management of forest for quick-growing, short-lived species like balsam fir.

As the world became more intertwined, with pulp and lumber now travelling further as a raw product, the margins got smaller.

Smaller sawmills closed their doors.

The same year hurricane Edna wiped out the shipyard Lawrence George MacGillivary went out on his own – yarding logs out of the forest with a horse and selling them under his own name.

When Scott Paper opened its doors, he became one of its first contractors in northern Nova Scotia, slowly mechanizing and building his operation.

His wife cooked for the teams of men, primarily from Spencer’s Island, that stayed for a week at a time in the bunkhouses on the Red River.

By age 10 his grandsons, Dwayne and Matt, were driving skidders – big wheeled machines that drag logs across cutover country.

High investment, high debt and narrow margins

The brothers have followed their grandfather’s lead since taking over the company a few years back, adding machinery and developing the advanced skillset required to operate and repair complex and expensive gear.

It’s high investment, high debt and narrow margins with about 98 per cent of what they cut being bought by Northern Pulp (formerly Scott Paper).

If Dwayne tells an operator of a harvester to take that job offer out west because the future is grim here, he can put another butt in its seat.

But it’ll take months of running the equipment before the new operator can do so efficiently enough to be making rather than costing the company money.

Peter Spicer grew up in the woods too, but along with Pat worked as a teacher in the k-12 school in nearby Advocate Harbour. He taught, among others, the MacGillivary boys.

When his father died 16 years ago, Peter quit teaching and went in the woods fulltime.

He and Pat cut small patches and narrow paths through their 650 hectares.

Though the Spicers and MacGillivarys practice different forms of forestry – both send their logs and pulpwood in the same directions.

From Spencer’s Island, that’s a long trip.

Farthest from the big pulp mills, Cumberland County doesn’t boast a single large sawmill.

That’s despite, according to the province’s registry of buyers, producing nearly twice the wood fibre of any other county in Nova Scotia. In 2017 Cumberland County sent out 521,000 cubic metres of sawlogs and pulpwood.

Silviculture work along with cutting and trucking wood are big employers for the area’s hardscrabble rural economy.

Woodlands, passed down through generations, often serve as savings accounts.

Pat and Peter get about $67 a tonne for the sawlogs he cuts and she winches out with the tractor.

Trucking takes $22 a tonne.

“If the price goes down at the sawmills because they’re getting less for their woodchips, then its not going to be worth cutting for us,” said Peter, 62.

“Sixteen years ago we were getting $74 a tonne.”

Selling woodchips, a byproduct of turning lumber from round logs into rectangular boards, to the province’s two remaining pulp mills accounts for an average 10 to 20 per cent of most sawmills’ bottom lines.

If Northern Pulp shuts, that takes just over a million tonnes of demand out of the equation.

Port Hawkesbury Paper consumes up to 600,000 tonnes annually depending on the markets for their shiny paper product used in magazines and flyers.

The expected outcome in the industry is that if Northern Pulp shuts, Port Hawkesbury Paper will cut back its own harvesting operations in Cape Breton and northeastern mainland Nova Scotia and offer to buy chips at a significantly reduced price from what’s being paid today.

For its part, Port Hawkesbury Paper isn’t saying and perhaps, like everyone else, doesn’t know what the future will hold.

“We have always and will continue to take a balanced (and) diverse approach to wood procurement,” mill spokesman Andrew Fedora said in a written response to questions on its plans.

“We have very specific requirements regarding species type, wood freshness and fiber strength.”

Pat and Peter Spicer and Dwayne and Matt Gillivary also don’t know what the future holds for them.

But they all worry the current impasse means continued decline for Spencer’s Island.

Beyond what to tell his employees, Dwayne also wonders what to tell his son who is graduating this year from the Maritime College of Forest Technology.

“You have to keep carrying on,” said Dwayne.

“You can’t just doom and gloom and let that get to you.”

RELATED:

- N.S. wants more information about Northern Pulp wastewater plan

- Northern Pulp expects waste treatment facility won't be ready by deadline

- Premier calls on N.S. fishermen to end blockade of pipeline survey vessel

- Boats to block Pictou Harbour all week, say fishermen opposed to effluent pipe

- Cleanup continues after effluent pipe leak at Nova Scotia pulp mill: minister

- Forestry industry watches Northern Pulp situation

- Pictou landing must be consulted on new treatment plan, judge says

- Ottawa mulls federal assessment of Northern Pulp

- Both sides struggle to control tensions as Northern Pulp closure looms

- EDITORIAL: Nova Scotia stuck in the muddle with Northern Pulp dilemma